How Saturated Fat Became the Villain: A Historical, Scientific, and Political Deep Dive

- S A

- Aug 5, 2025

- 4 min read

For decades, saturated fat has been public health enemy number one — blamed for clogging arteries, raising cholesterol, and fuelling the heart disease epidemic. From butter and red meat to coconut oil and cheese, foods rich in saturated fat were cast as dietary villains, while vegetable oils and low-fat snacks were marketed as heart-healthy alternatives. But how did we get here? Was the science ever that clear?

The story of how saturated fat became demonised is not just one of nutritional science, but of selective data, political momentum, industry influence, and public health oversimplification. Along the way, we went from nuanced debates in the lab to sweeping dietary guidelines that reshaped entire food systems — and possibly contributed to the very metabolic crisis they aimed to prevent.

In this blog, we’ll unpack the full timeline — from Ancel Keys and the Seven Countries Study to modern reevaluations of LDL cholesterol and ApoB. We’ll explore the key studies, the policy shifts, and the growing realisation that saturated fat may have been wrongly accused. Understanding this history isn’t just about setting the record straight — it’s about reclaiming a more accurate, metabolically informed view of what truly drives heart disease in the modern world.

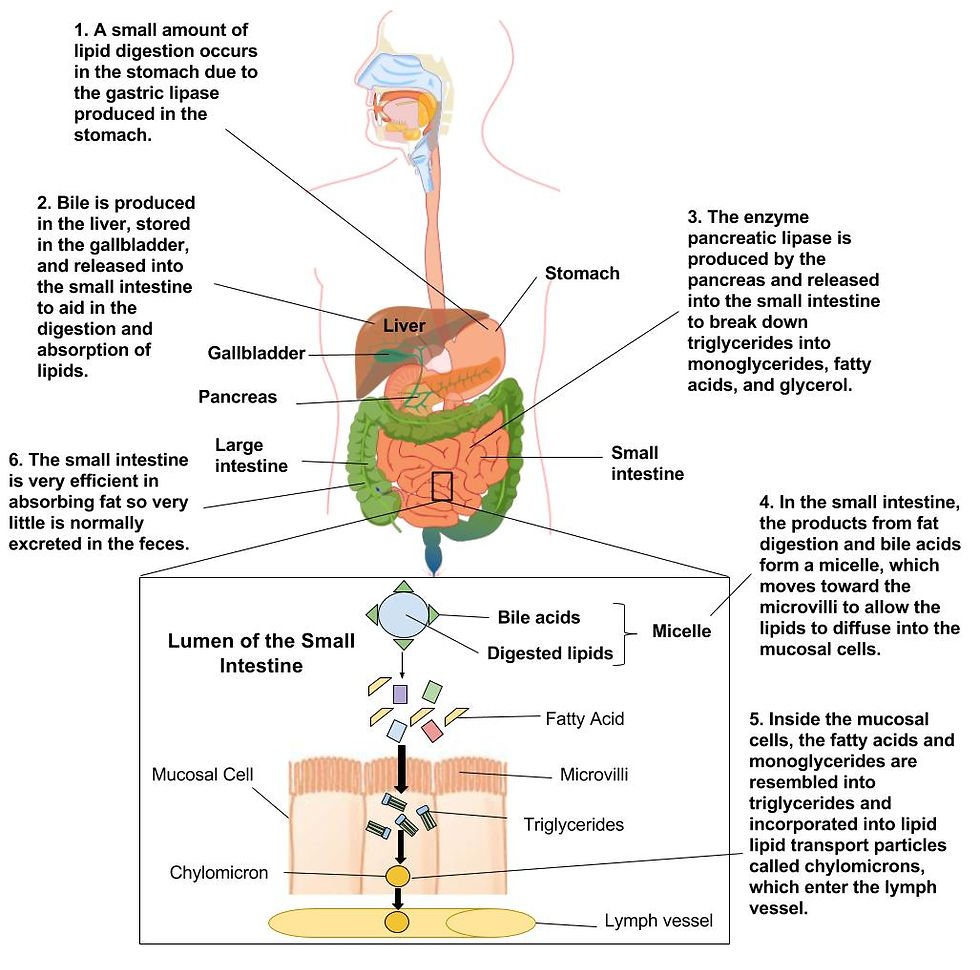

Image Credit: ResearchGate

Here's a breakdown of why saturated fat got its bad reputation — and what we now know:

Historical Basis:

Ancel Keys and the Diet-Heart Hypothesis (1950s): Keys proposed that saturated fat raises blood cholesterol, which increases the risk of coronary heart disease. His Seven Countries Study showed correlations between saturated fat intake and heart disease in certain populations.

Cholesterol Theory: Saturated fats were found to raise LDL ("bad") cholesterol, which was linked to the development of atherosclerosis — fatty plaques in artery walls. This supported the idea that reducing saturated fat could reduce heart disease risk.

Timeline: How Saturated Fat Got Its Bad Reputation

Year / Period | Event or Development | Impact on Public Perception & Policy |

1910s–1930s | Heart disease begins rising in industrialised countries | Initial concerns about diet and lifestyle emerge |

1953 | Ancel Keys publishes his paper linking fat intake to heart disease (using selective data from 6 countries) | Saturated fat becomes a prime suspect in coronary heart disease (CHD) |

1958–1970s | Seven Countries Study launched by Keys | Shows correlation between saturated fat intake and CHD mortality — but later criticised for cherry-picking data and ignoring confounders |

1961 | AHA (American Heart Association) recommends reducing saturated fat and cholesterol intake | Official start of fat-reduction dietary guidelines in the US |

1977 | US Dietary Goals advise cutting saturated fat and increasing carbs (especially grains) | Saturated fat is publicly demonised; carb intake soars in population |

1980s–1990s | Massive push for low-fat, high-carb diets; food industry creates fat-free but sugar-laden products | LDL-C becomes the central metric for heart risk; seed oils marketed as “heart healthy” |

2000s | Rising obesity and metabolic disease despite lower saturated fat intake | Scientists begin questioning the low-fat dogma |

2010 | Meta-analyses (e.g. Siri-Tarino et al.) find no consistent link between saturated fat and heart disease | Sparked renewed scientific debate |

2014 | Time Magazine: “Eat Butter” cover story | Public sentiment begins to shift; backlash against dietary guidelines grows |

2020s | Focus shifts to insulin resistance, inflammation, particle size (ApoB, sdLDL) rather than total cholesterol | Nuanced view of dietary fat and heart health gains ground — but public policy lags behind |

Modern Understanding: More Nuanced

LDL Particle Size Matters: Not all LDL is equally dangerous. Saturated fat may increase large, buoyant LDL, which is less atherogenic than small, dense LDL. Many now argue that focusing on total LDL oversimplifies the issue.

HDL Increase: Saturated fat also tends to raise HDL ("good") cholesterol, which helps remove cholesterol from arteries — a potentially protective effect.

Total Diet Quality Matters: Replacing saturated fat with refined carbs or sugar may be worse for heart health. However, replacing it with unsaturated fats (like olive oil or nuts) may reduce risk.

Recent Meta-Analyses: Some large-scale reviews (e.g., 2010, 2014, 2020) have failed to find a strong link between saturated fat intake and heart disease, especially when confounding factors are accounted for. But this remains controversial, as some studies and guidelines still support the traditional view.

Saturated Fat vs. Heart Disease: Summary of the Missteps

Misstep | Reality |

Correlation = Causation | Early studies showed correlation between saturated fat and heart disease, but ignored confounding variables (e.g. sugar, smoking, lifestyle) |

All LDL is bad | Large, buoyant LDL from saturated fat is less atherogenic than small, dense LDL from high-carb diets |

LDL-C is the best marker | ApoB and LDL particle number and type are more predictive of heart disease risk |

Low-fat = Healthy | Replacing saturated fat with ultra-processed carbs or seed oils may increase heart disease risk |

Seed oils are heart healthy | High omega-6 intake may promote inflammation, oxidation, and endothelial dysfunction |

Current Consensus (as of 2024–2025):

Mainstream health organisations (e.g., AHA, WHO) still advise limiting saturated fat (usually <6% of calories), but also emphasise dietary patterns rather than focusing on single nutrients.

There's increasing recognition that ultra-processed foods, inflammation, insulin resistance, and metabolic health are more reliable predictors of heart disease than saturated fat alone.

Conclusion: Time to Re-examine the Narrative

The vilification of saturated fat wasn't born out of malicious intent, but from early scientific theories that seemed logical in their time. However, as we’ve traced through the decades, this narrative was built on fragile foundations — from observational studies with unadjusted confounders to dietary guidelines shaped more by politics and industry than by solid mechanistic evidence.

In the process, saturated fat became a convenient scapegoat, while the role of refined carbohydrates, ultra-processed foods, and chronic inflammation in driving heart disease was largely overlooked. The result? A public health crisis defined not by fat overload, but by metabolic dysfunction — rising obesity, insulin resistance, and an explosion of lifestyle diseases.

Today, with modern lipid science, metabolomics, and deeper insight into insulin dynamics and inflammation, it's time to question the one-size-fits-all dietary dogma. Is saturated fat truly harmful in all contexts? Or have we misunderstood its role — especially when consumed as part of a metabolically healthy, whole-food diet?

In the next blog, we’ll go beyond the history and tackle this question head-on. We’ll explore the current science of saturated fat, cholesterol metabolism, and what really drives atherosclerosis — diving into lipoprotein biology, particle size, ApoB, inflammation, and the surprising protective mechanisms that emerge in low-insulin, low-inflammatory states.

Comments